The global village

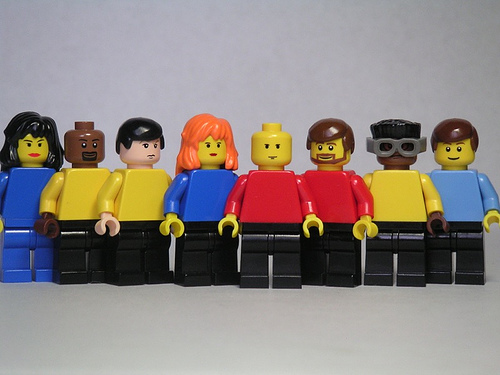

Multiple cultures at work

In contexts ranging from multinational corporations to social networking, leaders and their teams interact, communicate and influence others in multiple different cultural settings simultaneously.

What is ‘culture’?

One definition of ‘culture’ that provides a useful starting point is the one espoused by Philippe Rosinski, executive coach and specialist in leadership development in intercultural contexts. Rosinski talks of a group’s culture as ‘the set of unique characteristics that distinguishes its members from another group’ (‘Coaching across Cultures’, Nicholas Brealey Publishing 2003).

Culture goes far beyond national or even regional or local differences. While of course it can relate to geographic boundaries, it encompasses literally anything which characterises a particular group: age, gender, cognitive ability, personal style, industrial sector, profession, family, organisational ethos, faith and observance, pace of working …. The list is endless. It manifests in behaviours, values, attitudes, judgments, decisions and expectations.

Complex, diverse workforces

With increasing globalisation, workforces are becoming more diverse and more complex, as they embrace employees from a broader and broader range of cultures, who interact within increasingly complex systems. The leader’s task is to release his or her workforce’s capability in the interests of fulfilling the organisation’s agenda. Included in the scope of the qualities that characterise high-quality leadership, how sophisticated are our expectations of a leader’s capacity to lead a multi-cultural workforce in this very broad sense I refer to here?

How insightful are leaders seeking their next career step – or indeed headhunters and search firms – in terms of recognising this capacity as a key talent or a key skill for 21st century leadership? It demands self-awareness, the recognition of moments when we – and those around us – are making assumptions about those who are different from us, or missing the value in that difference, or failing to release it as a benefit that will drive an organisation forward.

The systemic impact of culture

It also requires a willingness to explore the systemic impact of culture in its widest sense: if working at speed, for example, is a characteristic of an organisational culture, how does that manifest itself in expectations, assessments that leaders make of their people, the quality of outcomes, or the effectiveness of communication? How are people’s contributions judged? Is there room for flexibility and what might be the benefits of that? Does reflection – sometimes referred to as the richest form of learning – have a place?

Google: a global culture

Take Google for example. Google is one company – and there are many in the technology space– that is populated to a very large degree by extremely bright people under the age of 30. The company recruits young, ambitious self-starters and original thinkers (see Harvard Business Review). So it’s a company with few baby-boomers (those born between about 1946 and 1964), some from Generation X (born between the early 1960s and the early 1980s) and many more from Generation Y (early 1980s to the early 2000s). It’s a global organisation, with a distinct organisational culture.

Globalised responses

Google needs to understand and respect the structured approach of the German as well as the more spontaneous style of the Italian, the individualistic North American as well as the group-orientated Japanese, the ‘always-on’ Generation Z 18-year-old and the loyalty-driven 55-year-old.

It may be populated by staff from a limited age range and intellectual capability, but it needs to speak to and respect an audience of literally all ages, worldwide, from youngsters to silver surfers and beyond (a surprising number of 90-year-olds are Internet savvy).

Leadership qualities for a global culture

It needs leaders who can engage their people in increasing their emotional intelligence (and especially their empathy) and versatility in their communication styles, who are self-aware enough to know when they’re making judgments that aren’t necessarily well-founded, and who can perceive their environments from a systemic viewpoint – i.e. to understand that they operate within a complex and constantly-moving web of relationships, multiple histories and influences.

If they – and others like them – don’t have leaders with this skill, they risk seeing only a small number of perspectives and thus failing to appreciate the essentials of their environment. That can make the difference between sustainable, well-rooted success and short-lived, superficially-based outcomes.

Photo by Andrew Becraft via Compfight